New York-Presbyterian Hospital fails to accept 9/11 Health Program

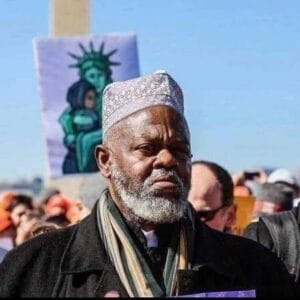

Former NYPD traffic supervisor Walter Clark has nothing but good things to say about New York-Presbyterian Hospital and the care he received for his 9/11-related double lung transplant.

However, the bureaucratic nightmare that comes with it because the hospital won’t accept a health plan covering Ground Zero survivors is another matter altogether.

First established in 2010, the World Trade Center Health Program provides screenings and treatment for more than 100,000 responders and workers suffering from 9/11-related illnesses.

Covered conditions range from respiratory diseases, digestive disorders, cancers, and other ailments caused by exposure to toxins that drifted over lower Manhattan for months after the collapse of the Twin Towers.

The idea behind the program is not just that it treats ill heroes, but relieves them from the stress of navigating notoriously difficult rules of insurance providers. Clark doesn’t get that break.

“It makes me upset,” said the 61-year-old former executive officer for the city’s traffic special operations division.

Like thousands of others, Clark helped with the recovery efforts at Ground Zero after the attacks on the World Trade Centers on Sept. 11, 2001 – and got caught in the poisonous clouds that emerged from the collapsing skyscrapers.

“I covered my eyes and covered my face with my shirt because I started not to be able to breathe, and everything got really dark and warm, which was a very crazy feeling,” Clark recalled.

Initially, Clark didn’t sign up for the WTC Health Program because he seldom got sick. He never really thought about the health impacts of being exposed to the deadly dust at Ground Zero even though he was surrounded by a toxic cloud and continually breathed in harmful particles for weeks.

He went about his life and work directing traffic operations at every major city event and emergency, even after he started passing out in 2015. He was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, a likely death sentence unless he could get a transplant.

Clark received his lifesaving lung replacement in 2017 and realized he needed to join the federally funded program which covers all related 911-health costs. But with New York-Presbyterian not participating in the plan, unlike most city hospitals, he routinely shells out co-pays for himself, often $200-$300 a pop for prescriptions and follow-up visits, resulting in thousands of dollars of out-of-pocket medical expenses.

“I can’t, from one minute to another, figure out what [New York-Presbyterian] is doing,” Clark said.

“Do they accept it, don’t accept it? Who’s covering this, who’s covering that? Which is which? I don’t know. That’s what’s upsetting.”

When health officials and members of Congress complained about New York-Presbyterian’s policy last year, administrative officials insisted that Ground Zero aftermath patients do not have problems dealing with the hospital. They also said they intend to become what is known as a “9/11 Health Program Clinical Center for Excellence,” which would end the bureaucratic problems.

On Thursday, a spokesman for New York-Presbyterian did not directly address the logistical and costly difficulties for sickened responders. He hinted at the lack of progress, saying only, “We are continuing to work on this issue and hope to have an update soon.”

Clark is not alone in his experience of dealing with the Manhattan-based hospital, which continues to rebuff the 9/11 Health Plan.

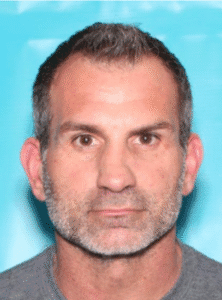

Charlie Buttacavoli, exposed to the deadly dust in lower Manhattan while working on high-power voltage lines for Con Ed, got stage-four tongue cancer that metastasized in 2011. He was left fighting side effects, including radiation damage to his arteries that restricts blood to his brain.

His wife, Pat, found a cardiologist near their home in Westchester affiliated with New York-Presbyterian, but the billing was a nightmare similar to Clark’s experience.

“They wouldn’t accept that coverage,” Buttacavoli said, adding he had to rely on his own insurance and Medicare, which didn’t cover everything.

“New York-Presbyterian has always been a problem with the payments,” said Pat Buttacavoli, who handles all that paperwork for her husband.

“I can spend, on a bad week, 30 to 40 hours trying to get his bills paid.”

Buttacavoli’s problem was solved when his cardiologist dropped New York-Presbyterian for another hospital in White Plains that accepted the federally funded program. According to her estimates, they still need to collect about $1000 from New York-Presbyterian.

Benjamin Chevat, who runs the 9/11 Health Watch, said it was particularly galling that the hospital told members of Congress last year that long-running problems didn’t exist.

“It is disturbing that the Board of Directors of New York allows their Chief Executive to say, ‘To our knowledge, no patient has ever been turned away or had difficulties accessing our services,’ when their staff has known about these problems since at least 2014, and have done nothing to fix it,” said Chevat.

He said there’s a simple solution.

“They can fix it today by simply signing a master agreement with the World Trade Center Health Program the same as other New York medical institutions have done,” Chevat said.